Dispatchability, Not Vibes: What PJM Market Monitor Gets Right—and Misses—on Data Centers Flex

What to Know and How to Talk About It

The market monitor is absolutely right about one thing: the way PJM’s demand-response products work today is not a substitute for real capacity. They’re voluntary, they’re called only in emergencies, and PJM doesn’t have a clean way to force an individual factory or data center to turn down at 7:13 p.m. on a Tuesday just because the grid needs it. From that vantage point, “flexible load” looks like wishful thinking. If that’s the only model you know, then of course you conclude that big new data center loads have to be matched with new generation, full stop. What they are not really engaging with is a different model, where the obligation sits on the grid-facing resource, not on the retail customer. Think of a “controllable load resource” as a power plant in reverse: instead of ramping generation up and down, it ramps consumption up and down, following dispatch instructions from the control room. It has a nodal obligation, telemetry, performance penalties, and all the same enforcement machinery that a generator does. Behind that single point on the grid, the operator is free to use whatever flexibility stack they’ve engineered—batteries, UPS systems, on-site generation, pre-cooling, workload shifting—to keep the customer’s 99.999% uptime intact while still honoring the grid dispatch. Basically, this latter framework is possible today only in energy-only constructs like ERCOT and non-RTO areas where dispatch curves can be designed to dispatch a load as a resource, which is why Yours Truly is leading the initiative to bring it to life in Texas. I think we can get there in PJM too: the technology to perform this solution will beat the creation of the market design to achieve it, is where the real barrier is at. Which seems to always be the case when it comes to tech and energy policy timelines.

Learn more below.

A.S.F.

The Alarm Bell PJM Is Ringing

PJM’s market monitor is sounding a very loud alarm about large new data center loads, and it’s worth taking seriously.

Their basic argument is straightforward: if you add a massive amount of new, around-the-clock load to the system without adding real capacity, you make the grid less reliable and more expensive. Full stop. In their telling, a lot of the current proposals to “solve” this with clever demand-side constructs amount to a regulatory fiction—papering over a capacity problem with accounting tricks.

They are particularly skeptical of any idea that says: “Don’t worry, the data centers will be flexible.” In the current PJM framework, “flexible” almost always means “emergency demand response”—something that’s called rarely, that customers can often say no to, and that the RTO cannot truly enforce on specific facilities at specific nodes. From the market monitor’s vantage point, that is not capacity. That is wishful thinking.

And on that narrow point, they’re right.

How the Monitor Sees the World: Voluntary DR and Cost Shifting

If you read the report through their eyes, all the proposals in circulation in PJM fall into two unconvincing buckets.

The first bucket is the demand-side option: treat the data centers themselves as a form of emergency demand response. Let them bid load reductions into capacity or energy markets, and hope that when the system is stressed they turn down in sync with PJM’s needs.

The monitor’s critique here is blunt. These demand-response constructs are effectively voluntary. Penalties are weak. Performance shortfalls can be washed out in later test events unless they occur during a narrow band of emergency conditions. And critically, PJM doesn’t have a clean, direct authority to tell a particular data center at a particular node to reduce load at 7:13 p.m. on a Tuesday and be confident it will happen.

Layer on top of that the reality that data centers are building for 99.999% reliability, with complex contracts, hyperscaler SLAs, and enormous commercial stakes. From where the monitor sits, it is not credible to assume that the same asset will quietly act as a deeply reliable, frequently interruptible resource whenever PJM is short on capacity.

The second bucket is the bilateral and co-location schemes—the “bring generation with you” family of ideas. In these constructs, a data center pairs itself with existing plants through bilateral contracts, reclassifies certain units as “new” through investment, or wraps itself around local generation and argues that this should change how it’s treated in the capacity market.

The monitor’s response is that all of this simply shifts costs. If existing plants are pulled out of the shared capacity pool and dedicated to a specific load, every other customer now depends on a thinner margin and will end up paying more until new generation is actually built. They predict chaos in price formation and reliability if this path is taken at scale.

From that vantage point, the only thing that “really works” under today’s PJM rules is a load queue for big data centers, paired with a fast-track interconnection path for those that come with truly new generation matched to their profile. You either wait, or you show up with supply.

If that’s your mental model, “flexible load” and “voluntary DR” collapse into the same thing: a nice-to-have, not something you can rely on for capacity. I wrote about this on LinkedIn months ago, check out the article: “There is no rational clearing price at which it makes economic sense for a hyperscale data center for AI to engage in market-based load curtailment — not when the cost of interruption exceeds the value of any demand response payment by orders of magnitude. That... is pretty much writing on the wall when uptime itself is the business model.”

The Conceptual Gap: Flexibility vs Dispatchability

This is where the debate needs to move.

Right now, PJM’s market monitor hears “flexible load” and thinks “optional participation.” That’s because they are looking at the demand-response products they actually see in the market today: emergency calls, limited hours, soft obligations, and weak enforcement.

The shift I am sponsoring in ERCOT is very different: it would allow large loads to voluntarily elect to behave like a power plant in reverse—fully dispatchable at the grid interface, with the flexibility stack hidden behind it. Once you do that, you’re not asking the grid to trust vibes; you’re giving it a resource it can actually dispatch and enforce.

That distinction is critical. There is dispatchability of load as an ISO-facing resource, and there is unenforceable “flexibility” that only constrains capacity design.

In the model I’m talking about, the obligation sits at the RTO interface, not on the retail customer in isolation. Think of a controllable load resource as a generator flipped upside down: instead of ramping megawatts up and down on the supply side, it ramps consumption up and down at a node, following the same security-constrained dispatch signals, with telemetry, performance metrics, and penalties calibrated accordingly.

Behind that single point on the grid, the operator can use any flexibility stack they’ve engineered—batteries, UPS systems, on-site generation, pre-cooling, workload shifting, storage, DER portfolios—to honor those instructions without compromising the end-user’s uptime requirements.

From the RTO’s perspective, that is not voluntary “flexibility.” That is a dispatchable resource with a binding obligation. And that is the piece largely missing from the PJM conversation as the monitor has framed it.

Two Kinds of Incentives: Prophylactic vs Speed to Power

There’s also a second gap in the conversation: how we think about incentives.

Today, the grid already has a kind of prophylactic incentive structure. If you tie into the system as a large, inflexible load under the status quo, you will be forced to curtail for reliability at some point, often on terms you didn’t design, after years of transmission studies and ad hoc crisis management. That’s the “you will bend when we’re desperate” model.

The ERCOT path I’m working on aims to create a very different incentive structure. Parties that choose to have their load comply with ERCOT instructions are motivated by earlier energization and better access to the grid, not by a stack of demand-response payments.

We’re saying, in effect: if you’re willing to show up as a controllable resource—take nodal dispatch, follow base points, expose telemetry, accept an enforceable performance regime—we will study you differently. We will be able to energize you faster, because you’re arriving with a built-in, engineered flexibility stack that we can see and model, instead of as a black-box liability.

That flips the logic from “paid to volunteer occasionally” to “rewarded with speed to power for assuming real obligations.”

Why the Market Monitor’s Skepticism Still Matters

None of this means the market monitor is wrong about the flaws of today’s demand-response constructs. The PJM IMM report is a hard indictment of the status quo, and I think that’s appropriate.

They are pointing at real problems that have already cost customers billions: emergency DR products that over-promise and under-deliver; planning models that treat non-firm DR as if it were firm capacity; cost-shifting schemes that shuffle existing plants around instead of building what’s actually needed.

It is not the market monitor’s job to speculate about the future. Their mandate is to guard the integrity of the markets we actually have today.

But that also means we should be careful not to mistake a critique of today’s fragile DR scaffolding for a blanket indictment of all load-side dispatchability. They are describing a world where the only levers on the demand side are voluntary, weakly enforced, and structurally mismatched with the scale of the problem.

Our job, as an industry, is to build something different.

ERCOT Planning Guide Revision Request 134

That’s what we’re trying to do in ERCOT.

We are designing a category of ERCOT nodal grid participation where large loads can voluntarily opt into behaving like supply-side resources at the grid edge.

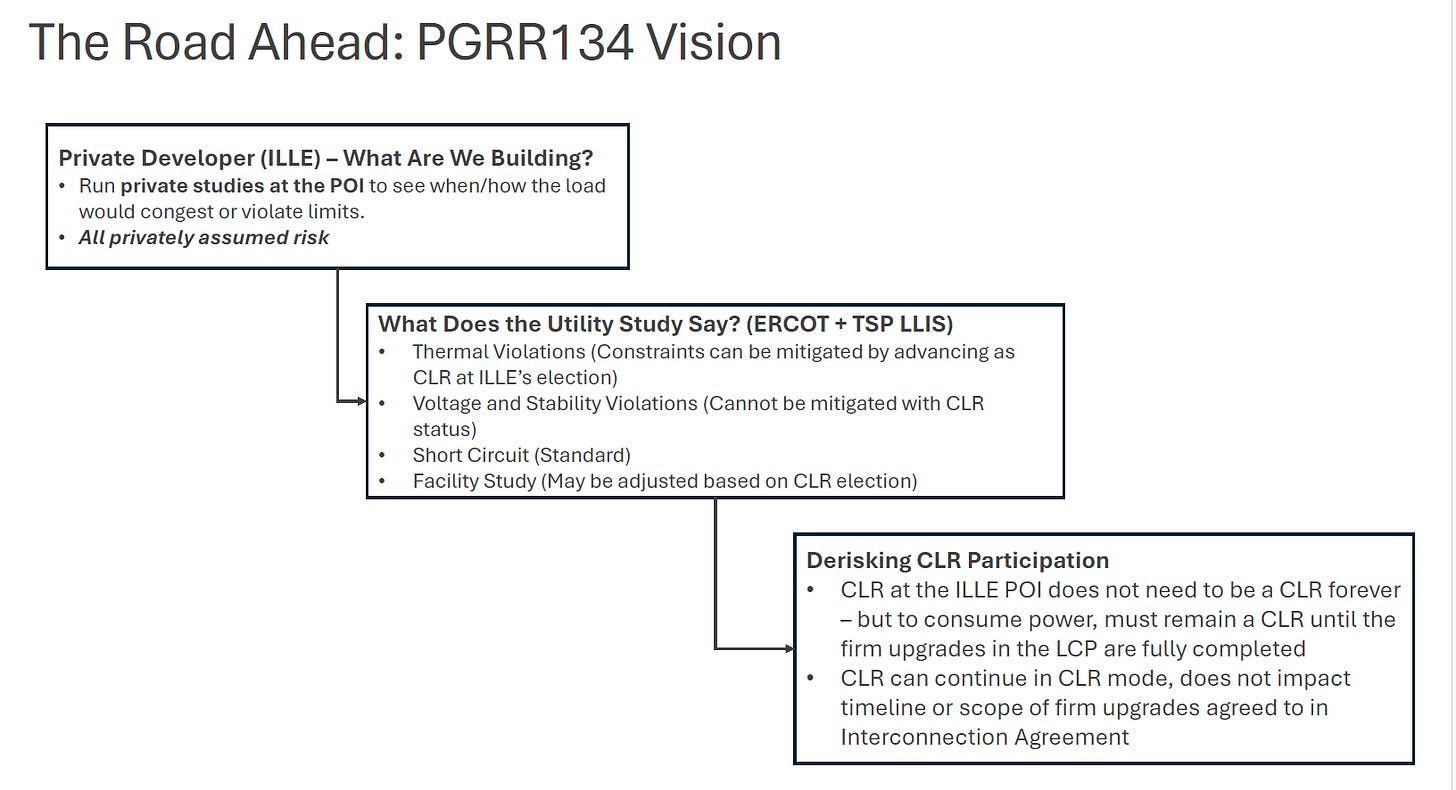

They elect into this category; they take on a dispatch obligation; they expose real-time telemetry; they submit to performance penalties and settlement rules; and they architect their sites—through a mix of storage, on-site generation, UPS design, and workload orchestration—to make that feasible without sacrificing their business. Here’s what the proposed path looks like:

In return, CLRs get an opportunity to energize earlier in the same “connect and manage” paradigm that governs the market’s participation of generators and batteries. Speed to power becomes the primary incentive for participating on these terms, not just incremental demand-response revenues.

From my vantage point, dispatchability at the load’s site controller is an essential element of getting this right. A robust control architecture that can translate RTO instructions into safe, predictable internal actions is a bridge between grid reliability and data center reliability, instead of a tradeoff. In my view, AI workload design teams will begin designing this solution anyway, because Texas already has mandates under Senate Bill 6 that require large loads seeking grid power to develop a clear safety path to protect (privately firm or safely shift) compute power draw if they are curtailed at the utility breaker.

Can PJM Get There? Not Overnight, But Yes

I’m not naïve enough to think PJM can perfect this on a short timeline, given the legal and institutional constraints it operates under. Retail–wholesale jurisdiction splits, state oversight, and the legacy of how DR has historically been structured all matter.

But we can absolutely get there.

Across the industry, capital and brainpower are already flowing into the control systems, commercial structures, and demonstration projects that make true speed to power the real incentive: if you’re willing to be dispatchable, you get to the grid faster and on clearer terms.

That’s the future the PJM market monitor is not obligated to imagine—but we are obligated to build. The real debate is not “generation versus flexibility.” It’s “firm, enforceable dispatchability versus the soft, voluntary notion of flexibility that has clearly failed us.”

Once we center that distinction, the path forward becomes clearer: honor the IMM’s critique of the current DR fiction, and then move beyond it by redefining what it means for large loads to be part of the reliability toolkit. Not vibes. Not voluntarism. Actual dispatchable resources, engineered from the ground up to support the grid they depend on.

The monitor keeps treating “flexibility” and “demand-side” as synonyms for “effectively voluntary,” because they’re looking at today’s emergency demand-response programs. In that world, PJM is begging large customers to cut load a few hours a year under extreme conditions, and the customers can say no. What we’re talking about is fundamentally different: a contracted, dispatchable resource at the RTO interface that is required to respond, just like a generator, and that has engineered its internal operations so that those grid obligations don’t show up to the end user as random outages.

That distinction matters a lot for AI and data centers. If you assume the only lever is “turn the data center off when things get tight,” then you’re right to be skeptical—no one is going to build a multibillion-dollar campus on that basis. But if you recognize that the data center can arrive with its own flexibility toolkit—storage, fast backup generation, smart workload management—and expose that to PJM as a dispatchable resource, then it stops being just a giant new load. It becomes part of the reliability toolkit, as long as the RTO can see it, dispatch it, and hold it accountable.

So the disagreement isn’t about whether today’s demand-response rules are flimsy. They are. The disagreement is about whether we freeze the world in that shape, or update the rules to let controllable loads sit under the same kind of hard obligations as supply-side resources. The monitor’s paper is diagnosing real problems with the current DR products, but it is not yet wrestling with this newer category of load that is engineered from the ground up to be dispatchable in planning and operations. I just wrote about what that is, and what it will be: flexible AI factory reference design is already here, and soon it will be built into the ecosystem of responsive assets which PJM could rely on with the right market design to enable resource-specific dispatachable participation.

A Post-Script: Loads in PJM and Loads in ERCOT Dispatch Differently - Flex in Interconnection Planning Makes Sense Today in ERCOT

The situation of controllable loads in PJM is similar to ERCOT in that there are mechanisms for loads to participate in the wholesale market and act as resources, BUT - PJM controllable loads (Demand Response) are not currently subject to nodal dispatch, while ERCOT’s NPRR 1188 (already passed and going live within the next 2 years) aims to specifically implement nodal dispatch and pricing for Controllable Load Resources (CLRs). The work that we are doing in Texas rides on the implementation of a rule that literally requires controllable loads to behave the way generators behave and get redispatched by SCED, and be bound to CLR rules (including only being allowed to telemeter the out status when it is not consuming- it can’t just opt out of participating).

A bit more about ERCOT and how a data center is a “retail load” and also a nodally priced and settled (at wholesale) CLR: the CLR’s QSE acts as anintermediary, managing the nodal market exposure (the wholesale LMP) while the data center’s retail bill reflects the contractual price negotiated with the REP. For many of these large loads, the contractual price is already very closely tied to the real-time wholesale LMP to encourage them to respond to market signals.

The distinction is between the financial relationship with the REP and the market settlement relationship with ERCOT.

Their QSE’s transaction with ERCOT for the energy they consume is calculated at the Nodal LMP of their specific electrical bus. So, they are wholesale metered (EPS/IDR meters). They are not using the standard Texas retail settlement for small customers (Load Zone Settlement).

Dispatch and Settlement Granularity in PJM, by Contrast:

Dispatch: PJM can technically dispatch individual Demand Response resources (especially large, single-site resources like a data center) when they clear in the capacity or energy markets. However, the dispatch signal is generally driven by system-wide needs or zonal congestion.

Settlement: Demand Response is settled based on the Zonal Locational Marginal Price (LMP) or a sub-zonal price. They are paid for their load reduction at this wider area price, not the precise nodal price of their facility.

The Aggregation Challenge described by the Market Monitor as an impossibility under current rules:

PJM’s DR Resources: PJM’s DR is often made up of an aggregation of many smaller end-use customers (C&I businesses, schools, etc.) that are bundled together by a Curtailment Service Provider (CSP) to meet the minimum MW requirement to participate.

Lack of Nodal Registration: These aggregated resources are typically registered across a wide PJM Zone or Sub-Zone. The current PJM rules do not require these resources to provide their specific, individual nodal location as PJM’s Market Monitor has noted - that requiring nodal dispatch is inconsistent with the current aggregation and registration rules. (You can’t dispatch a resource by a node if PJM doesn’t know the resource’s specific, verifiable location on the transmission grid.)

More later - join us at Planning Load Working Group’s Nov. 18 meeting to learn more about how we’ll work together - as a market with ERCOT - to shape a viable solution that works for stakeholders in Texas.

A.S.F.